An odyssey of paid refills

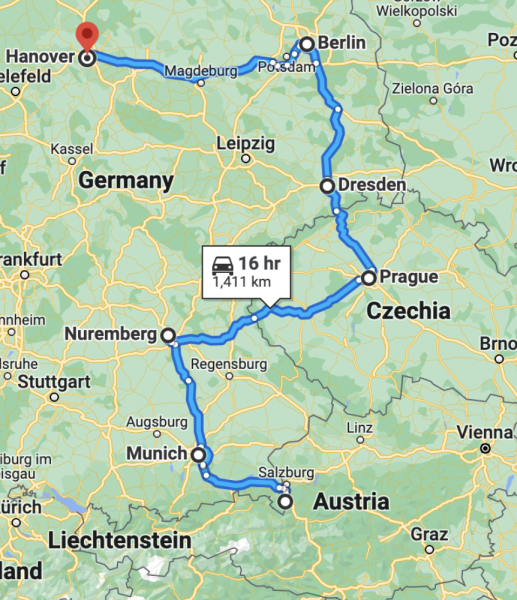

In early June 2023, a contingent of four teachers and 28 students (with representation from all classes, including rising freshmen) took a nine hour flight from Austin to London and then caught another plane heading to Munich, Germany. This was the beginning of this year’s World War II and Cold War History Trip, the first of which took place in 2004. These trips, bringing students to museums, memorials, and other locations of great historical and cultural significance, are led by faculty member Mr. Perry, the Director of Outdoor Education and a fluent German speaker. Mr. Chung, Ms. Gibbs, and Dr. Armentrout also came along for this two-week journey throughout central Europe, which covered roughly 876+ miles across Germany, the Czech Republic, and parts of Austria. I would be remiss in my retelling of this trip if I failed to also mention our primary tour guide, Peter Wild. Peter is a retired drama teacher from Somerset, England, who has accompanied the school on the past four history trips to this region. Often imitated by other guides but never quite replicated, Wild brought both British humor and a brisk walking pace that revealed a slowness in St. Stephen’s students, both in understanding his comedy and in physically moving from site to site on our walking tours.

One of the more significant one-on-one interactions I had with Peter was after dinner one night in Nuremberg. Dinners, on this trip, were included in the cost of the trip…meaning that students didn’t have to pay for their own dinner directly. This dinner, however, was pivotal in my friend group’s understanding of the world at large – about a schism in dining so great that it really makes you thankful (and quite patriotic) that the United States got this one thing right.

Let me set the scene. My friends and I had a table of about 6 to ourselves, adjacent to the faculty table. We’re eating potatoes and pork chops in some sort of dimly-lit, quite hot basement of a restaurant, and we’re all a little bit thirsty. We had finished all of our drinks – our Fantas, Cokes, and waters – till our cups were empty. Our waiter, crouching down ever-so-slightly as to not hit his head on the ceiling, swings by to ask us if we need more drinks. Unintentionally embodying the “ignorant American tourist” stereotype, we ask for a second round of drinks. We shortly get our drinks, finish our meals, and head back up and onto the hotel. We were about to pass through the exit of the restaurant before we got stopped by Peter – who held two receipts in his hand, both of them long enough to put most CVS receipts to shame. Here’s what we would come to find out in the next few moments: there’s no such thing as a free refill on soft drinks in Germany (or Europe, or really the rest of the world outside of the United States for that matter), and that Peter was surely not going to foot the additional €40 drink bill that us students had run up (perfectly reasonable and well within his rights). Small issue: we had very little European currency on us and Peter wanted to be repaid then and there. As we attempted to find a way to repay Peter with the chump change we had in our pockets, we formed something of an interstudent economy, in which IOUs were both drawn up and torn down, debts were bought and sold, and primitive currency exchange between dollars and euros took place. Rest assured, though, that Peter was repaid – and that not a single glass more of soda was refilled on his or the school’s dime.

From on high

If you could distill the entire WW2/Cold War trip into a single main idea or question, it would be “What does it mean to move on?” Every historical site linked to the Nazi Party or Holocaust that we visited on this trip appeared to have a slightly different answer to this question, whether that answer involved building museums and memorials to remember the past, or letting old buildings rot away and diminish these works of evil, or razing structures and forgetting about them entirely. The maintainers of the Kehlsteinhaus thought it best to renovate it and turn it into a restaurant.

The Kehlsteinhaus (also known as the Eagle’s Nest) sits atop the mountains of the Berchtesgaden Alps at an elevation of 6,017 feet (1,834 m), providing visitors with majestic views of the natural beauty of southeast Germany – a sort of serenity that contrasts its sinister history. The Eagle’s Nest’s primary use was as a meeting space for Nazi Party officials, having been visited by its highest-ranking members, including Adolf Hitler himself.1However, Hitler didn’t really spend much time at the Eagle’s Nest at all. Reaching the Kehlsteinhaus requires what may be one of the most terrifying bus rides of your life – a five-ish minute journey on a specialized vehicle that takes you up a winding road around and inside of the mountain the Kehlsteinhaus is built on. A laughingly short barrier runs alongside the road, all of the way up to the top, and is supposed to keep the bus from plummeting off of the side of the mountain. Every jolt and sharp turn that the bus made seemed to remind us that we could totally fly off of the edge at any given moment. The path up seemed to have been built at a remarkably steep incline, too, adding even more adrenaline to this short bus ride. Even after all of this, we still had to ride an elevator up to the top of the mountain as the bus could only go up so far. While I had heard that the Kehlsteinhaus had some food and drink options up there, I had no idea that most of the building had been converted into a restaurant. This is the Kehlsteinhaus’ primary function today – serving the appetites of tourists who flock to this popular historical site. If you’re looking to see the building in a preserved state as it was ~80 years ago, you would probably be disappointed. There’s very little presentation of the building’s history up there, aside from a few plaques scattered throughout the premises telling visitors what the gist of the Eagle’s Nest was. What the Kehlsteinhaus lacks in historical context, it makes up with stellar views of the lush Alp mountains. Evidently, this approach of dealing with the Eagle’s Nest has worked well for the charitable trust that maintains the building, which has leagues of visitors that flock to it every season – tourists that can grab a quick bite in a building of now-palatable evil.

More on moving on

If you take a stroll through central Dresden, you will surely note the wonderful displays of German Baroque architecture on every corner – whether you’re looking at the marvelous Frauenkirche (the “Church of Our Lady”) or glancing at the colorful facades that line the plazas of the Neumarkt (“new market”) section of the city. Museums, opera houses, water fountains. As you walk around for a bit longer, you may even consider how perfect Dresden appears – the perfectly paved walkways, the prestinely-white stone and marble that make up the buildings you pass through, and the uniform red roofs that appear to have every single tile intact. In every street lamp, in every etching chiseled on to every building, and in every single muntin and mullion separating every window pain, there’s no grit. No struggle. You’ll start to realize that you’ve stumbled into a town that – in the paraphrased words of our tour guide – is infatuated with its past. Specifically, Dresden’s history prior to 1945. Before Dresden was, in February of that year, hit with the might of more than 2,600 tons of bombs dropped by British and American airmen, ultimately culminating in a firestorm that killed 25,000-40,000 German civilians. The “terror bombing” of Dresden is considered by some historians today as a war crime that provided questionable strategic value to the Allied powers at the cost of many civilian casualties.2It is important to note that there are varying historical interpretations on the justification(s) for the firebombing of Dresden. Some modern historians, like Frederick Taylor, argue that its destruction was necessary because the city served Germany as an important industrial center and was a hotbed of Nazi support. Oppositely, historians such as Jörg Friedrich have written on how the bombing of Dresden was not necessary in the slightest. However, the Dresden of today would rather you not know that about its own terrible destruction. In fact, its lengthy, post-war reconstruction has embraced a romanticized version of Dresden – one that might not have ever really existed.

In the next articles in this series, you’ll hear more about Dresden and what it’s like to stay in a hotel built explicitly for classic East German Stasi surveillance. You’ll also hear about close encounters with death via the trams of Prague. You’ll also hear about the smashed shop windows of Berlin and the struggles of an art scene as gentrification takes hold of the capital city of Germany. Stay tuned!