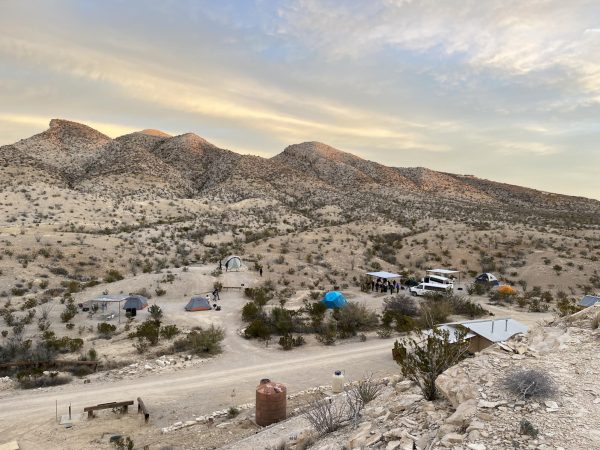

Last month, thirteen students and four faculty members traveled for about eight hours on a van ride from Austin to Terlingua, a ghost-ish town that finds itself near the Texas–Chihuahua border. The mission of the journey? To find dinosaur remains. We, after all, had taken up the opportunity to participate in the last-ever West Texas Paleontology Trip. For over two decades, the Science Department at St. Stephen’s has sent groups of paleontologically-curious students into the Chihuahuan Desert through this program with the hope of furthering humanity’s knowledge – specifically, the anatomical knowledge of the creatures that roamed the Earth more than 60 million years ago.

Getting from Austin to Terlingua is one journey; getting from base camp to the dig site is another. Nearly all of the “roads” taken to get to the dig site are largely unmaintained dirt paths that zig-zag across the uneven desert terrain. To say that the ride was bumpy would be an understatement. Some of the potholes we encountered on the ride truly challenged the integrity of the school vans’ suspension as we rolled right over them – the vehicle shooting up, leaving us passengers weightless for a split second, then crashing back down…the engine sputtering as Mr. Mohlman or Mr. Dolan hits the accelerator pedal, the tires kicking up dust as we move forward through the lonesome landscape of the Terlinguan desert. Out there there’s nothing but ocotillo cacti, hogs, and rock (which really behaves more like dirt than anything else – it breaks away as soon as you put any of your weight on it).

Those who have been on this trip know that there’s no sort of paleontological hand-holding when you’re out west. It’s not like you’re at a kids’ exhibit at your local science museum, where you’re digging up plastic fossils in a sand pit with plastic mini-shovels. What there is, though, when you’re out in the West Texas desert, is rock – and lots of it. To be a paleontologist in Terlingua is to have your patience tested by rock. You swing at it with your pickaxe, it breaks up, and then you move it aside with your shovel – and you try to see if the fossil you’ve been searching for has been lying in the matrix1No, not like the movie. Matrix is any sediment that is attached to a fossil. beneath your feet this whole time. And you breathe it in – the fine, particulate matter that the rock kicks up as you shift it around. This is the process that you repeat over and over again. If fortune has it in for you, then you’ll hear it before you see it: the sound of your steel tool striking a fossil. This is the rewarding part of the often-Type II fun2While an activity classified as Type II fun may be grueling in the moment, it is something that you can look back on with pride and satisfaction once you’ve gotten through it. that is digging for dinosaur remains.

So you’ve found a fossil. Now, you are burdened with the task of trying to remove all of the ancient dirt and sedimentary debris that is joined to your fossil. Good luck. The challenge here becomes one of trying not to break a 60-million-year-old fossil while trying to remove the matrix from around it. The tools-of-the-trade for fossil extraction that our guides swore by were items that you could easily acquire at any grocery store: toothbrushes, knives, acetone, paper towels, and tin foil. First, toothbrushes and knives can be used to slowly remove all of the surrounding matrix from the fossil. (This process can take quite a long time. It’s important to take your time when trying to remove the matrix…you don’t want to accidentally shatter the fossil into a million pieces.) Second, an acetone mixture can be applied to the fossil in an attempt to keep it together as it is pulled from the ground. Third, paper towels and tin foil can be used to securely store the fossil, which by this point, has probably broken into a few pieces.

One reason why this was the last West Texas Paleontology Trip is because the land has been exhausted. Generations of St. Stephen’s students – as well as amateur and professional paleontologists alike – have come through Terlingua and have extracted tons of fossils over the past few decades. Finding a fossil has become increasingly difficult in the past few years because there simply aren’t as many fossils in the ground anymore as there once were. This isn’t to say that this last trip was unsuccessful – in fact, it was quite the opposite. With the assistance of Scott Clark and Glenn Freeman, who served as our paleontological guides, our team was able to recover three fossils. We believe that we found a vertebrae, a tarsal, and a humerus bone – all likely from a hadrosaur3Hadrosaurs – known as “duck-billed dinosaurs” – roamed around North America throughout the Late Cretaceous Period, which was about 100.5 million to 66 million years ago. So, chances are, we were looking at some 66 million year old fossils.. Our guides had a keen eye and pointed out that, on one of the fossils we recovered, there were actually marks from an alligator bite right on the bone. After all, the desert that we were standing on was actually a swamp-ish, partially aquatic environment all those millions of years ago. You would have no idea about this part of the desert’s past, though, because of how absolutely parched the whole place is today. It is in this barren Chihuahuan Desert that we break past the scorched dirt to uncover fossils, one by one…so that we may better understand what roamed here long before our time. This is what makes the challenge worthwhile.

I would like to thank the wonderful faculty members that made this trip possible: Mr. Dolan, Dr. Furman, Mr. Mohlman, and Mr. Perry. They took on the ultimate challenge…driving a bunch of rowdy high school students for eight hours across the state of Texas. And they let us order several rounds of wings without complaint at Long Draw Pizza. And several Mexican Cokes. All on the school’s tab.